TREK REPORT 2009

> Home > Volunteer treks > Trek report 2009

Women's health, vaccine fridges & solar lighting

C Brian Smith

Trek objectives

This trek spanned the period 16 March to 6 April 2009 (Kathmandu to Kathmandu) and we had the following objectives:

• pay the salaries of the healthcare worker at Ghunsa and the pre-school

teachers are Ghunsa and Folay

• conduct a program of women’s health assessment and education using

a questionnaire and an educational video (see REPORT)

• check that the vaccine fridges at Tellok, Mamankhe, and Ghunsa were

operating properly

• install a solar-powered lighting system in the gompa at Lelep.

The plan, therefore, was to fly to Biratnagar, Nepal's second city, drive to Tharpu, trek to Folay and Ghunsa via Tellok

and Mamankhe, take time out to visit to Kangchenjunga Base Camp, then return via Lelep and fly from Suketar back to Biratnagar.

The plan didn't allow much spare time, but we achieved all the objectives, and Rob and Rachel reached Kangchenjunga Base Camp

and saw Kangchenjunga itself. Rachel's report on the women's health programme is here.

The principal use of KSP funds on this trek was the payment of salaries.

The team

My companions were Rob Rowlands, a director of KSP, Rachel Gentile, an aspiring medical student, Bishu Tamang, a young Nepali

from Kathmandu, who would translate for Rachel. My role would be to help Rob with electrical work.

Bishu's father, Purbar, had played a major role in building the school at Folay and the dormitory at Lelep, so the trek had a

special significance for Bishu.

Staff

KSP hires staff for its treks. In this case we had a guide “GB”, a cook, “MB”, a kitchen boy, Sambu, and a Sherpa (general

helper) “CK”. These staff, provided by Kanjiroba Ltd, came with us from Kathmandu. GB hired porters locally as required.

We had up to five at a time.

The official routine was for us to pack our bags before breakfast so that GB and CK could take down the tents and the porters

could assemble their loads. GB would then serve our breakfast, after which we’d begin the day’s trek, carrying with us packed lunches.

GB, as guide, would stay with us during the day (although Rob had traversed the route many more times than he had), but the

other staff and porters would overtake us and establish the next camp. MB and the kitchen boy (carrying the kitchen),

especially, would go ahead to set up the kitchen and perhaps buy food locally. Our tents would be erected and waiting for us

at the end of the day, and MB would prepare us hot drinks for us as we arrived and, later, dinner.

So, at times we had nine people looking after us four, and often I felt uncomfortable being waited on. (Although it is nice

to have someone prepare a meal!) But it soon became clear that having staff was critical to the program. We had a tight

schedule and the staff saved us time. They enabled Rachel and Bishu to conduct their women’s health education, and Rob and

me to work on the fridges and lighting without having to worry about the usual camp chores, cooking, etc. As well, they

enabled us to carry a vast array of equipment essential to the program — a video player, tools, test instruments, etc.

Getting started

Starting the trek was not a simple matter. Initially, our plan (“Plan A”) was to fly to Biratnagar then trek from Tharpu,

as outlined above. However, we shelved this plan when we heard that continuing strikes had closed Biratnagar airport. Plan B

was to fly instead to Tumlingtar and trek via Milke-Danda. But, when the day came day, the strike was lifted and Biratnagar

was the only airport not closed by weather, so we reverted to Plan A.

At Biratnagar (236 feet ASL and 30°C), we hired a 4WD vehicle, which, thanks to a substantial roof rack, managed to take all

of us plus our mountain of gear. For most of the next four hours we journeyed across the flat plains of the Nepalese Terai, but

in the last hour we climbed to Ilam, which at 2627' is free of mosquitoes.

The next day — billed to be the worst — began early. After a quick breakfast of eggs, toast, and tea, we climbed

into a second 4WD vehicle and left at 6.45am. The driver from the day before had refused to go beyond Ilam, and the reason soon

became apparent. The road was very rough — worse than some off-road driving — and required quite different driving

skills from those for speeding across the congested Terai. And, the rougher road was much more wearing on the vehicle.

During a rest stop, we watched a sadhu at work apparently helping a young man into the after-life by an elaborate

procedure involving a small chicken, a decorated bamboo pole, and a large audience. The local cheese factory was

surprisingly well stocked.

At Phidim, we lunched on dahl baht (lentils and rice) then turned off the sealed road and endured about four hours of

winding and bone-shakingly rough road to reach Tharpu at 4.30pm. On this section of road, our top speed (reached only

occasionally) was 20km per hour.

Day 1: Tharpu to Tellok

The Tharpu hotel was noisy, and we were pleased to start trekking at 6.45 am. The trail descended steeply into the Iwa

Khola (river), crossed it on a substantial swing bridge, then turned into the Kabeli Khola and followed it upstream,

arriving eventually at Tellok. This took all day, and we arrived at Tellok around 6 pm.

Women's health program

At the first village, Sinam, Rachael's women’s health and education program began in earnest. She and Bishu fell into

conversation with Chandra Kala Khadka, a woman who lives at Ambegudin and was going our way. She was interested in Rachael's

video and went ahead to assemble a group of women to view it. Later, at her house, as we drank black pepper tea, nibbled

roasted soy beans, and washed off some of the grime from the trail, women began trickling in, eventually forming a very

satisfactory audience of 18. Rachel augmented the video with explanations and answered questions, using Bishu as an

interpreter. Men were excluded from this performance, to their apparent chagrin.

Further up the valley Rob called in on Prem Bahadur Rai, who had provided accommodation on an earlier trek. Rob took

photographs - Prem’s wife needed them for a passport — and later, in camp, printed them on a battery-powered photo printer.

Throughout the trek the printer was a source of immense entertainment and was a key means (along with personal photos and

Hindi videos) of building rapport with the communities KSP aims to assist. The demand for passport photos was surprising,

but many Nepalis go to the Persian Gulf to work.

Throughout the day the weather was hot and dry and the trail dusty. The terraced paddies were mostly empty, although some

had crops of maize, wheat, and barley. Rice would be planted prior to the monsoon rains in May. That night, there was

spectacular lightning and thunder, but only a little rain. More rain would have been welcome (and we got it) as it would

clear the hazy atmosphere. Occasional gusts of wind fanned fires visible on the other side of the valley. These fires had

caused considerable damage and we passed a couple buildings — which have timber frames — that had been destroyed. Along the

way, we spotted large pods hanging from trees, which proved to be the source of bathroom loofahs.

Rachael's first "class", Ambegudin

Day 2: Tellok to Mamankhe

First vaccine fridge

Breakfast was at 8.00 am, after which we climbed for about 20 minutes to Tellok’s health post, which opened at 10.00 am.

Rachel talked to the healthcare worker and local women while Rob and Brian checked the vaccine fridge. Unfortunately, it was

not working. The fridge runs off a battery, which is charged by a solar cell. A controller prevents the battery from being

overcharged, but in this case the controller had failed and the battery had boiled dry. As well, the fridge’s thermostat and

motor controller had both failed, so the only things left working were the solar panel and health post's lights (during the

day). The only likely explanation for such widespread damage seemed to be a lightning strike. One of the batteries had also

been damaged physically. Rob replaced the controller while I disconnected the damaged battery and refilled the remaining

one. The battery was then re-connected to the solar panel and appeared to be charging satisfactorily. However, we were not

equipped to replace the faulty fridge components, so we could only take notes of what was required and promise to get them

repaired.

Next to the KSP fridge was a brand new fridge supplied by Unicef. But this fridge ran on kerosene, which the community

couldn’t afford, so the fridge had never been used.

About 12.15 pm, we set off or Mamankhe, descending into the Sikheba Khola below Tellok, then ascending steeply, regaining

the height of Tellok in about two hours. We stopped for chia (tea) and lunch, then headed south and climbed through

Yangpang, interrupting the prize giving as we passed the local school. (The headmaster couldn't hold the children's

attention after we'd hoved into sight.) We stopped for tea again, at Phumphe Danda, and reached Mamankhe just on dark.

We’d had some afternoon showers en route, so the local school was a welcome alternative to tents.

Day 3: Mamankhe to Chherengdanda

Next morning, we inspected the Mamankhe health post. Despite the apparent wealth of the village, it was a pretty meager

establishment, and the fridge there had not being working since February. The fluorescent room light was also not

working.

One of the solar panels had been damaged. The healthcare worker suggested that a large landslide and flying rocks were

responsible, but as the roof was not visibly damaged, a small boy with a stone seemed a more likely story. Despite the

damage, however, the solar panel was still working. The battery-charging controller (replaced by kiwi friends the previous

October) was functioning perfectly, and the batteries were apparently in good condition. The fridge motor was operating,

but the fridge itself was not getting cold. Rob diagnosed loss of refrigerant, which again was not something that we

could fix, so we had to content ourselves with replacing the room light.

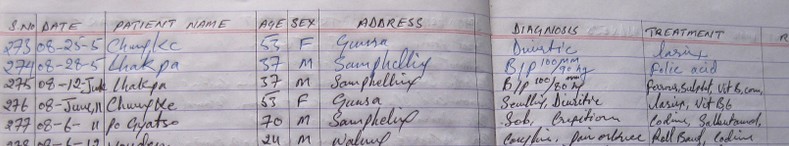

Meanwhile, Rachel and Bishu examined the health records and held court with a woman who arrived for a look-see with her

three young children.

Abandoned aid

We left Mamankhe at about 10.30 am and soon passed a museum — a large structure, about the size of three houses. In Rob’s

experience, this had never been open. The next stop was to inspect a small hydro-electric power plant, also not working.

These were graphic examples of wasted funds — funds supposedly for tourism and community development — wasted through lack

of continuing maintenance.

We sidled up the Kabeli Khola valley, ascending steadily and passing just occasional wayside houses. Then, we descended

and passed through a small patch of laurels and cardamons. Cardamon is a significant crop in Eastern Nepal, and in the

first few days we saw numerous porters transporting large sacks of cardamon bulbs down valley. Cardamons are always found

growing under laurel trees, with which they seem to share a symbiotic relationship.

A few minutes after crossing a small wooden bridge, we turned left and climbed for about 10 minutes to a Sherpa friend’s

house, at Chherengdanda. This was a delightful spot. The house was set apart from neighbors and looked out on terraces

of wheat, potatoes, chives, and cabbage-like greens. Three or four cows grazed under a mat-roofed enclosure. We arrived at

3.00pm, so it had been a short day (4:30 hours).

Chherengdanda

Day 4: Chherengdanda to Deurali Danda

A high pass

This was to be a big day. From the Sherpa’s house the track climbed steadily towards Deurali Danda (ridge), a high pass

at 11,400’. At about 6600' we noted a potential camp site for future possible use, and at 8500’ we rested for about

20 minutes at a cowherd’s shelter. Completely surrounded by dung and evidence of recent slaughtering, it wasn't a place

to linger. By 10.50 am, we were at 9700' and had seen violets and other flowers, tiny strawberries, rhododendrons, and,

in a narrow altitude band, flowering magnolia trees. Our speed slowed as the altitude increased, but we made steady

progress. The route was dry, except for a single stream crossing at almost 10,000', which made an ideal lunch spot.

Despite the cold water, Rachael washed her hair.

First snow

We reached Deurali Danda at 2.00 pm. After a clear morning, it was then hailing lightly, and Bishu had seen her first

snow — track-side remnants of a snowfall perhaps the night before. A rough shelter stood on the pass, but it was no

incentive to stay, as a more substantial hut was waiting just 10 minutes down the other side, at 10,900’.

This hut’s disadvantage, apart from draughts, was a lack of water. Rob and I descended into a small creek, but were

reluctant to go down too far, not having anything to carry water in (and the effort of climbing back up was considerable).

Later MB and GB went down a long way and staggered back with perhaps 30 liters. We collected wood and made a good fire in

the hut, but it was a cold night in the tents.

Day 5: Deurali Danda to the Ghunsa Khola

From the Deurali Danda hut, we descended to Hellok, losing all the height we’d climbed the day before. After three hours

we were down to 8800’ on a trail that led through rhododendron and cedar forest. Locals fell the straight-grained cedar,

split it on site, then cut it to a standard length for use as for roof tiles — by those who cannot afford corrugated iron.

We saw a deciduous variety of daphne in flower.

Hellok is not a rich village compared with nearby Lelep, being north-facing (inferior crop growing conditions) and spread

over about 2000 vertical feet. We arrived at “mid Hellok” at 1.00 pm after a seemingly interminable descent of steep rocky

“stairs” and stopped for lunch. Rachael and Bishu soon found an audience and had a good healthcare session, again with

about 18 women. Rob charged batteries.

Flat batteries

Battery charging for the team’s various cameras, Rob's laptop, and the video player was becoming a problem. Rob had a

25 watt flexible solar panel, which he could unfold and hang up using bungies tied to whatever was convenient. But with

early starts, relatively late finishes, and often mid-afternoon showers, charging time was limited to perhaps an hour at

lunch time — insufficient to keep everything functioning. The situation was relieved when we reached Folay, where we

could plug into mains power.

We left Hellok at about 3.45 pm and by 4.30 pm had reached at a good camp site in the Ghunsa Khola opposite

Sakethun.

Bishu using a flipchart to illustrate women's health, Hellok

Day 6: Ghunsa Khola to Jungle Camp

We spent this day and the next getting to Folay (spelled Phale on some maps), high up in the Ghunsa Khola, stopping at

Jungle Camp en route. The trail crossed and re-crossed the Ghunsa Khola five times, on increasingly rickety bridges, then

climbed to Amjilosa, where we had tea and admired the apricot blossoms. We'd been on the trail for six hours. On the way,

we spent half an hour for lunch by a stream, where the porters looked for frogs, the legs of which are a delicacy

(to them).

Picnic under hanging rock

Jungle Camp was an hour and three quarters from Amjilosa. It comprised a single house up against a huge rock overhang,

which provided convenient shelter from the afternoon shower. Three young children, surprisingly clean and well dressed,

were excited to see us. The boy, Chetin, 12, had just walked three days home from school in Taplejung. This family eked

out a living from a narrow terrace on one side of the river, which seemed to be for their few animals, and a small area

they’d cleared on the other side of the river, which they used for crops. A rickety bridge crossed the river in two

spans: none of us liked the look of it, but Chetin sauntered across with his hands in his pockets.

En route to Jungle Camp

Day 7: Jungle Camp to Folay

We left at 8.15 am and got to Gepla at 10.30 am, passing two Austrian trekkers on the way. During the entire trek, we

passed only one other trekker, but saw also a Spanish climbing expedition (at Ghunsa) — who had hire 95 porters!. From

Gepla, which is on a high terrace, we descended to the river and walked within a few metres of the raging torrent for

perhaps an hour before the track once again ascended steeply to another high terrace and the village of Folay.

By the time we arrived, the porters had settled into a room attached to a house cum restaurant and the GB and CK were

erecting the tents on a flat grassed area. MB had large plates of freshly boiled potatoes waiting for us. Rob had been

pining for these after days of rice (relieved twice by with pasta he’d brought from California).

Electricity

The house had one long room with restaurant-type tables at one end and a fireplace — the centre of activity

— at the other. Behind the fireplace was an impressive array of shining plates and bowls, aluminum pots of various

sizes, crockery soup bowls, and enamel mugs — they seemed to be symbols of status. Mains electricity, reticulated

from Ghunsa, was being used with enthusiasm. As soon as it came on, at 4 pm, the solar lighting was switched off, thermoses

were filled as quickly as the kettle would boil water, and Rob started charging batteries and printing photos — to the

excitement of a gaggle of grubby children. The electricity reduces the demand for scarce firewood supplies (and, of course,

is easier).

Day 8: Folay

It rained during the night and the morning was grey and gloomy, unlike other mornings, which had been fine. The rain

persisted, so we decided to stay a second night in Folay and delay the short hike to Ghunsa till the next morning. After

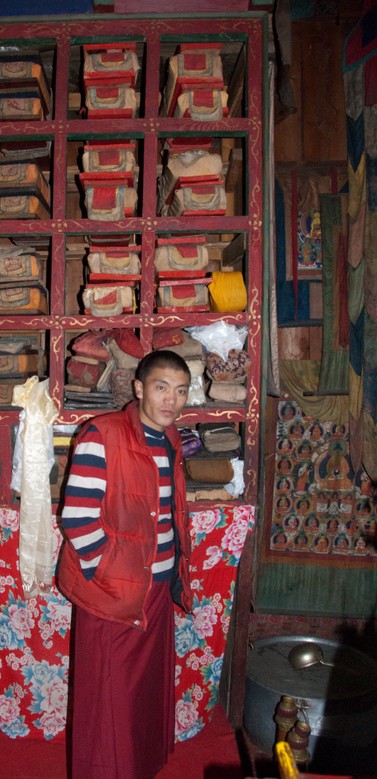

breakfast — eggs and pancakes - we visited the local monastery and were shown its various treasures by the two lamas in

residence. It smelled strongly on rancid butter.

MB excelled himself by serving hot cake and chips for lunch, after which we visited Folay school. Building this had been

funded by KSP and managed by Bishu’s father, Purbar. It includes a pre-school and a medical clinic. Folay is predominantly

Tibetan, and the school teacher's salary is paid by the Tibetan government in exile. On the other hand, KSP pays the

pre-school teacher’s salary, and this had to be renegotiated in the light of the fewer children attending since Rob’s

the last visit. Negotiations were conducted at our hotel with various representatives of the village, who decided amongst

themselves how many teachers were now needed, and with Rob over how much should be paid. Agreement earned a round of

applause and a written contract was executed with thumb prints.

The healthcare worker from Ghunsa, Tenzin, then arrived, despite light snow, and Rachel and Bishu showed the women’s

health video to a small group.

Day 9: Folay to Ghunsa

The water barrel was frozen in the morning, and the grey sky was forbidding as we set off for the monastery at 7.00 am to

attend the morning puja — lots of chanting by the lamas, plus the playing of the long horns (not unlike didgeridoos),

“oboes”, and a drum. Four old women preceded the ceremony by walking clockwise around the monastery numerous times, giving

the prayer wheels a spin on each circuit, but they didn’t attend the puja. During the puja, a young girl came in and

added milk to a container of perhaps millet flour — the lamas’ breakfast.

By the time we set off for Ghunsa, it was snowing quite heavily and continued throughout the day except for a short

clearance in the afternoon. It was an easy hour and a half walk. In Ghunsa, we checked into Himali Chungdra's guesthouse.

I went out to photograph the village, but the snow — 2-3 inches deep by this time — soon took the gloss off that

activity.

We visited the health clinic and met Tenzin again, then inspected a plant for distilling juniper oil and the

hydro-electric power station.

Patient records at KSP's Folay healthpost

Power station

The power station has a Pelton wheel, operating with a 70 metre head, and satisfies

a peak demand of about 42 kW. The operators started it for our benefit (it "rests" each day between 1 pm and 4 pm,

for reasons unknown), and Rob and I sorted out some of the mysteries of power distribution that had beset us the day

before. Voltage is controlled by running the system at full load and using excess capacity to heat a large tank of

water. As with so many innovations, the weak point of this scheme was again the continuing maintenance. The villagers

have only a one-year maintenance contract with the suppliers, and with only two months remaining the belt connecting

the Pelton wheel to the generator is already showing signs of wear. The operators say that this will cost Rp60,000

($US750!!) to replace. When it fails, Ghunsa and Folay will be in darkness until that money is raised and a new

belt acquired — a month at the very least.

Next, with Himali in tow, we visited Lamu, the Ghunsa midwife. KSP pays both her and Tenzin’s salaries. Rachael and

Bishu examined the birth records — birth control via injections seems to be working — while Brian and Rob discussed trade

and education with Himali.

Nepal-Tibet trade

Generations of Nepali-born Tibetans live in Folay and Ghunsa (and elsewhere) and trade with Tibet. They take yaks, yak

calves, and yak ghee to Tibet and return with wool, salt, shoes, Tibetan tea, rice, and Chinese manufactured products

(electrical appliances, solar panels, etc). There are two commonly used two routes to Tibet, one via Yangma and one via

Olangchunggola. The route via Yangma is shorter, but more difficult because of an icefall, so the longer route via

Olangchunggola is preferred. Normally, there is no difficulty getting into Tibet, but when China is annoyed about

something (e.g. the Olympic flame controversy), it closes the border. This poses a problem for Olangchunggola, which has

no agriculture and exists purely on the passing traders. On at least one occasion the Nepali government has flown rice in

to sustain the villagers there during a border closure.

Many Ghunsa children of the Tibetan-speaking Nepalis go to school in Folay, which instructs in Tibetan, but is limited

to five levels. For further education, they go to school in Darjeeling in India, or Gangtok or Kalampong in Sikkim. As

a result, they often speak quite good English. Tenzin was a case in point. She was born in Yangma and educated in

Kalimpong, before marrying a man from Ghunsa. From KSP’s viewpoint, she was thus an ideal candidate for healthcare

worker — well educated and able to communicate effectively in English. KSP funded her healthcare training —

six months in Kathmandu. While we were there, Rob paid her her salary for the next 18 months. However, that was not the

end of the story.

Day 10: Ghunsa to Kambachen

Yesterday’s snow lay 3” deep, crisp, and even. We left at 8.45 am, the snow slowing our progress somewhat. Sambu,

the kitchen boy, was wearing the long socks I'd given him in Folay. The track sidled up valley alongside the Ghunsa

Khola, passing through junipers and cedars. We stopped at a bridge over the Ghunsa Khola for a 20 minute lunch at

12.15 pm, then plodded on. We were at 12,600’. I was finding the increasing altitude difficult and lagged behind Rob

and the girls. Higher up, we climbed up to 13,700 to get over a slip and had to sidle across risky screes, but had no

difficulty. After that, it was down hill (mostly) to Kampbachen on a river flat at 13,400'.

Beyond habitation

Kambachen was an uninviting prospect. It felt cold, treeless, and deserted. In fact, it is only a "summer” village of a

dozen or so houses, and the residents retreat to warmer climes during the winter. Some of the houses had been damaged by

a recent earthquake. Currently, only two men were living there, both tending yaks. The snow had been melting, but still

covered the ground, and Sambu and one of the men were clearing spaces for our tents. Accommodation for the staff and

porters was meagre.

MB and GB went back to check on the porters, and things brightened up when they arrived in camp again. A thermos of tea

appeared, the tents went up, and we were ensconced in sleeping bags by 4.30 pm. Dinner was served in the tents.

Breakfast at Kambachen before setting out for Lonak. Mt Jannu in the distant top left.

Day 11: Kambachen to Lhonak

Unlike the gloom of the evening before, the morning was cold, clear, and crisp, and there was a fine view of the

mountains. We slothed in our tents until the sun hit them then had breakfast outside.

We packed and left at 9.40 am, a late start. Our objective was Lhonak (4785 m), a climb of 685 m. The route lay along

lateral moraines. It was straightforward, but gaining the altitude was difficult. But somewhere past Ramtang (4370 m),

MB served hot noodle soup and cheese, made over the primus in the lee of a waist-high stone encirclement. This did much

to revive us, as did the news that we were only 200m below Lhonak. The morning’s sunshine had given way to mist and a

stiff cold wind.

After the soup, we advanced to Lhonak seemingly easily. Lhonak is a grassed, sandy flat of perhaps five hectares, formerly

a glacial lake. It is home to six or eight stone huts, which are inhabited during the monsoon, when the dried grasses come

to life. There are no trees, so all the support and roofing timber must have been carried up from below Kambachen. Yak

dung is the only available fuel, but it burns remarkably well, although with a characteristic odor. We had access to one

of the stone huts, which was remarkably cozy once the fire was going.

Day 12: Kangchenjunga Base Camp

Again the morning was clear and crisp, but clouds were soon evident on our horizon, although they didn’t come to

much.

Rob, Rachael, and Bishu set off for Kangchenjunga Base Camp at about 8.30 am, but an hour or so later Bishu arrived back

feeling unwell. I knew I needed an acclimatization day, so opted to stay in camp.

Rob and Rachel took 3:15 hours to reach Base Camp, spent an hour or so there, then returned to Lhonak at about

4.00 pm. They got some views of Kangchenjunga, in between patches of cloud.

Day 13: Back to Ghunsa

A strong wind threatened the stability of the toilet tent during the night, but the morning was calm, clear, and there was

an inch of snow underfoot. This was to be another big day, going down in one day that that had taken us two days to come

up. We left Lhonak at 7.45 am, reached Kambachen at about 10.30 am (2.25 hours), where MB had organized a feed of freshly

boiled potatoes, accompanied by tea (black or Tibetan), then after an hour set out for Ghunsa. Although the downhill trip

was easy compared with the uphill slog, the rocky trail was tiring, and we were pleased to reach Ghunsa at 3.45 pm. It

was good to be back among the rhododendrons, cedars, and thicker air, although short uphill stretches reminded us that we

were still over 10,000’.

Alpinistas de Espańa

A Spanish expedition had taken up residence at Himali’s Hotel, so we moved into Nemu’s place next door. It had a fine lawn

for camping — continuously mown by two yak calves — and a hot shower, which proved popular. The shower room was a small

lean-to with a canvas bucket suspended from a rope. After filling the bag with hot water, turning the tap at the base of

the bucket started the flow. The floor was spread with leaves over which were laid a couple of planks to stand on. It was

altogether very satisfactory, except that the shower rose was only about waist high. At night, the lean-to served as a

stable for the two calves.

Part of the program was to uplift the solar-powered lighting system from the health clinic and transfer it to

Lelep — the clinic now being served by hydro-electric power. GB and Himali climbed on to the roof of the clinic and with

difficulty retrieved the solar panel. Himali claimed the steel pole supporting the now unnecessary wind generator —

he needed a new pole for his Tibetan flags. I dismantled the wiring inside the clinic, and Rob sorted through a large

bag of tools, cable, and electrical fittings left in the clinic from a previous trip.

Day 14: Jungle Camp again

There were a few things to be done before we left Ghunsa. Apart for printing passport photos for locals, the Spanish

expedition had asked for photos of their proposed route to be printed from Google Earth images. Two guys arrived with

their laptop, one of whom proved to be Carlos Soria, now 70, who had climbed eight of the world's 8000m peaks, including

Everest and K2, and was planning to climb the remaining six within the next five years.

Village politics

Rob instigated a meeting with the villagers to discuss the issue of the healthcare worker. For the past 18 years, the

position had been held by Pema Chembal Lama, who's lama status gave him considerable influence in the village. But, his

frequent absences from Ghunsa meant he was now unable to fulfill the duties as required, so KSP proposed that the role be

taken over by Tenzin and that she be paid the one salary available. Tenzin, who is a meticulous and intelligent young

woman, had received six months of training, funded by KSP, and was already providing healthcare six days per

week. Individually, those at the meeting recognised the merit of this decision, although they were reluctant as a group

to act without Pema Chembal Lama's consent, who was again absent. However, we were assured that we would meet Pema

Chembal Lama on the trail the next day, so the issue was left unresolved.

Back on the trail

After being presented with Tibetan silk scarves, Rob and I set off for Folay, about one hour away. Rachael and

Bishu had already left, as Rachel wanted to buy carpets there. Halfway there, we passed again the memorial to the 26

WWF dignitaries and crew killed in a helicopter crash in September 2006.

Rob paid the pre-school woman in Folay her wages, then in the early afternoon we set off for Gepla and Jungle Camp.

Light rain fell, and there was a brief thunder shower while we had tea at Gepla, 2:20 hrs from Folay. After Gepla,

the trail climbs and falls, crossing four side streams, and was laborious work. Time was short, and dusk was gathering

when we finally arrived in Jungle Camp, 1:20 hrs from Gepla.

One of our porters had wanted to remain in Folay, so GB had been forced to find a replacement. The man he hired

proved to be drunk, and he was long overdue in Jungle Camp by the time darkness fell. GB and CK set off in search of

him and were gone a long time before retuning, wet, but with the news that the porter would arrive soon. And in due

course he did, but his load was wet because he did not have, or did not use, the usual plastic sheet porters carry to

keep their client’s loads dry. The porter was in bad odorr.

We spent the evening in the sole Jungle Camp house entertaining the woman there and her children, aged about 2, 6, 10,

and 14, with photographs.

Day 15: Down to Lelep

The drunk porter did not want to continue, perhaps because of the previous evening's events, so he was paid off —

enabling him to buy more alcohol — but without baksheesh. There being no other option, he was replaced by Lapka, the

14-year-old from Jungle Camp. We were concerned that she should be carrying such a big load, but GB said he had

allocated her only one bag, "maybe 40 kg, so no problem". In the event, she swapped loads with Sambu, who carried

the more voluminous, but lighter load of the kitchen utensils. Of course, that meant that all the staff were carrying

extra loads. And, GB himself carried the solar panel — half a square metre in area and weighing several kg — by hand for

two days from Ghunsa to Lelep.

The trail from Jungle Camp climbs almost interminably to Amjilosa (1:45 hrs), where we stopped for tea, then descends

even further to the first of several river crossings, where we stopped for lunch (1:30 hrs). GB tied a silk scarf to the

bridge for luck, although there was another bridge further downstream where I thought the scarf might have been of material

benefit.

Pema Chembal Lama

Shortly after the bridge, we met Pema Chembal Lama, who was a young-looking 55, clean cut, smartly dressed, and

engaging. Fortunately, his wife had called him from Ghunsa (which now has a satellite phone), and Pema Chembal was

accepting, albeit reluctantly, of KSP's proposal regarding the healthcare worker, so the issue was resolved.

After lunch the trail again rose and fell and we had another welcome tea break after the last crossing of the Ghunsa

Khola. Up to this point we had been retracing our steps of the previous week. Now, we branched off and headed for the

final climb to Lelep.

Crossing the Tamur Khola

But the day’s vicissitudes were not yet over. We four crossed the bridge over the Tamur Khola and sat to rest on the

further abutment. As we sat, we saw MB approach the bridge, drop his load, and double up in apparent agony. Rachel and

Bishu re-crossed the bridge and found MB is great emotional and physical distress, apparently severely dehydrated,

and suffering from cramp. Given that the staff were all carrying heavier loads, this was not altogether

surprising.

I went on towards Lelep, caught up with my bag — the porters were carrying loads in shifts by now — and retrieved

some electrolyte replacement salts, which GB carried back to MB. Rachael administered these, along with Advil tablets.

MB, however, had a different diagnosis. He was convinced that the spirit of an old man who had fallen off the (previous)

bridge had entered his body, so he dispatched CK to find a lama and stopped midway across the bridge to throw money

into the torrent below.

Rachael and Bishu accompanied MB to the lama’s house, and witnessed a puja or exorcism of evil spirits. By

Rachael’s account, this involved three varieties of incense, ancient religious texts (instruction manuals?), peacock

feathers, various other religious objects, and was accompanied by incantations. MB was much helped by this, although

we westerners couldn’t help noting that his recovery coincided with when we expected the Advil and electrolyte to take

effect.

In due course MB continued on to camp and, never one to neglect his duty, was soon well enough to slaughter a couple

of chickens and produce another delicious meal of (fresh) chicken soup, chicken curry, rice, and dahl, albeit a couple

of hours later than usual.

Day 16: Lelep

At long last, this was to be a rest day and an opportunity to wash bodies and clothes. After breakfast of noodle soup and

apple cake, we climbed up to the health clinic and met the doctor, an engaging and apparently competent fellow dressed in

all-whites and looking ready for cricket. While Rachael and Bishu talked to him about health issues, Rob and I checked the

fridge. This was KSP’s first fridge project, which had been installed originally at Lungthung then moved to Lelep. Within

Lelep, the fridge had been moved again from the original health clinic in KCAP premises to a new building at the top of the

village. Despite all these moves and the less-than-optimum placement of the solar panel, the fridge was working correctly

and there was ice in all the right places. This was good news.

Lighting the gompa

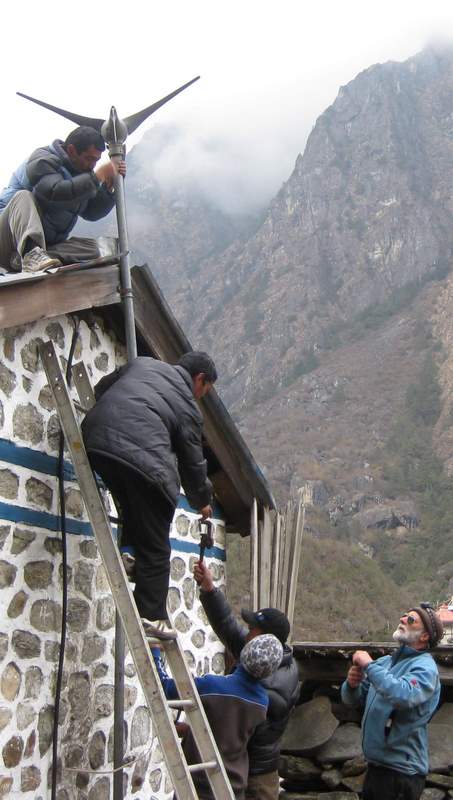

Next, we tackled the gompa lighting. GB had hand carried the solar panel from Ghunsa, and the porters had carried a 7 AH

battery, plus other paraphernalia needed to help the lama read his texts. Mounting the solar panel on the roof was the

first challenge. Rob asked me to do this, as he’d fallen off his own roof in California, so was a bit wary of repeating

the act in Lelep. The roof was precarious — made of about 22g corrugated iron that flexed alarmingly under my weight.

However, with GB’s and CK’s help, plus the help of someone inside the ceiling to thread nuts on to the screws I inserted

through the roof, between us we got the panel in position. Then we wired up the lights and mounted the battery and charging

controller. The lama was keen to help and took my cue on mounting the cable ties neatly and equally spaced. When we’d

finished, Rob took the requisite photographs, and the lama served tea and presented us with silk scarves. We felt

pleased to get the job done satisfactorily. The procedure was interrupted by lunch, which this time was potato slices

fried to crispness, puffed up cheese pastries, and vegetable curry — another remarkable meal prepared with simple

facilities.

Tourism troubles

Returning from the gompa, we passed by the house of the president of the Village Development Committee, who invited

us to drink more tea. Interesting discussion followed, especially on the subject of Lelep’s desire for tourists. To

Lelep's disadvantage, trekking guides have tended to bypass Lelep, using an old route on the other side of the river,

instead of the new route, which avoids a steep ascent, down which we were to trek the next day. Nice as Lelep is in many

respects, the camping area by Norbu’s hotel is unpleasant. It is used to graze animals (because there were no tourists),

and we found ourselves dining within metres of cows, goats, and chooks, and dealing with their attendant flies. It is not

a good look for tourists, and we made this point.

Day 17: To Linkhim

From Lelep, we began a long descent to Taplethok (2 hrs) and to bamboo, bananas, and buffalo. Near Taplethok the trail

had been “sealed” with a remarkable layer of rocks, mostly schist, many of which were large and had been split and the

exposed faces laid uppermost to provide a flat walking surface. While this was an impressive feat of construction, it

was nevertheless less easy walking than the sandy surface on which the rocks were laid.

After Taplethok, we climbed to Cheruwa (1:10 hrs), a hobbit-like tight cluster of houses and shops, set among gigantic,

house-sized boulders. There we could sit on an upstairs patio, drink tea, and admire the passing parade of people and

goods moving upstream, the goods apparently bound for Tibet.

Makeshift camp

From Cheruwa, we climbed continuously to reach Linkhim. We had hoped to camp in the school grounds, but the locals

were unwelcoming and refused to open the school for us. So, after some casting around, we camped in a wide portion of

the track, just near the village’s far entrance, which caused some interest among the local children and some disruption

to traffic. Fortunately, there was room to erect MB’s cooking tent — one of the few times we needed it. Rain started

shortly after the tents were erected, so we crouched in the cooking tent to eat.

Again there was a porter problem. Two had yet to appear, so GB and CK went back down the track to locate then and

returned about three hours later, again wet, but with the porters.

In Lelep, Lapka and her brother, Chetin, met up with their father, and GB hired him as a porter for the two days we

needed to reach Suketar. Lapka carried my big bag for these two days, a much more modest load than previously. Young

Chetin carried a tent, plus his own gear, and with his constant engaging conversation was voted the noisiest boy in

all Nepal.

Day 18: Out to Suketar

Much rain fell during the night, and tents and gear were wet when we packed up under a grey sky. From Linkhim, the

trail sidled and climbed steadily, passing small settlements, and descending at times to cross long suspension bridges.

We left about 8.15 am, but were delayed for a couple of hours by a return to locate a missing item of jewellery. Eventually,

the trail crossed a saddle at Jogidanda, and we stopped for tea and lunch. MB bought two roosters, which subsequently

traveled in Sambu’s doko of kitchen gear looking rather put out. We reached Suketar about 5 pm and booked into the

Kangchenjunga Hotel, adjacent to the airfield. The proprietress had a good fire going and hot tea was most welcome.

This was the final night of the trek, and MB excelled himself (again). He used an upstairs kitchen, from which a lot of

squawking emanated — then silence — as the meal was being prepared. We were served, (fresh) chicken (well, rooster)

soup, chicken curry, drumsticks, complete with napkins wrapped decoratively around them, and coleslaw. This was

followed, unusually, by dessert, a sponge cake, with an egg-white topping and an inscription in icing. MB had achieved

this all of this, including slaughtering and plucking the roosters, in a little over two hours using a single primus

stove, plus a shovelful of hot coals, which with a couple of wash basins he contrived an oven. It was a

remarkable performance.

Getting home

This was even more complicated than starting the trek. We were ready for check in at 6.00 am, but banks of cloud rolled

over the runway alternately lowering and raising our hopes of a plane arriving from Biratnagar. About 9.00am, there was

a flurry of activity. We were issued boarding passes (rather used ones), searched perfunctorily, and lined up at the

edge of the runway. The plane, a Pilatus Porter, arrived, circled several times, then disappeared, the cloud preventing

it from landing. We repaired to the hotel for omelet and chapattis and to reassess our situation.

Two charter flights were expected, and we had hopes of catching a back flight direct to Kathmandu. However, the

prospects seemed slim as the first was full and the second was cancelled. Or so we thought. The first landed, the cloud

having cleared, Rob applied his silver tongue to the captain, and suddenly Rachael had the one seat available to Kathmandu.

This solved the most pressing problem, as she had a flight that night to Hong Kong.

The remaining three of us, plus the four staff, set off down the hill for Taplejung, about an hour away. GB found a

hotel and the promise of a 4WD vehicle to Biratnagar next day.

Early start

Rob proposed an early start of 4.30 am, but as the vehicle wasn't due in Taplejung till about 1 am, the prospect of

us getting away on time seemed doubtful. But at about 4.45 am, with enough tooting to wake the town, the said vehicle

arrived, and an hour later we set off. The complete crew comprised us three, four staff, two drivers, a boy, and another

man who turned out to be the vehicle owner. It was a tedious journey, broken only to watch a truck being manovered back on

to the road after nearly tumbling over a precipitous drop. We arrived in Biratnagar about 9 pm. Finding a hotel with

vacancies proved frustrating, but eventually we checked into the Eastern Star. Meanwhile, mission control had been re-booking our flights (again) and we all arrived back in Kathmandu next day in time

for Rob's flight at midday.

Impressions

Although I'd been two Nepal twice before, I soon realized that, even by Nepalese standards, the Kangchenjunga region

is remote territory. The villages of Ghunsa and Folay are on the fringes of habitation. The people

there are tough and resourceful, but they lead hard lives eking out a meager existence and receiving minimal help from

central government. Facilities such as schools and clinics, despite KSP's efforts, are primitive.

The trek also brought home to me the scale of KSP's achievements. To organize the building of schools and clinics in

such a remote place, and with limited ability to communicate, is no small feat of guts and perseverance. I also began

to appreciate that schools are clinics are not one-off events. To be effective they must be maintained. That means not

just physical maintenance, but salaries for the people who teach and work in them, supplies of books, drugs, etc. And

that means regular and lengthy treks, such as ours.

En route back home, flying in a sleek 21st century aircraft, I felt that, in reality, we hadn't achieved a great deal

for all the time and effort we’d put in. Most of our time had been spent just getting there and getting home again. But,

as Rob pointed out, that is to overlook the less tangible, but equally important, outcome of maintaining contact with the

people KSP helps to serve. That contact — maintained by regular treks since KSP was created in the mid 1980s — ensures that

KSP's projects are useful to the villagers and have their support. And just how crucial that is became obvious when we

saw such things as the Unicef fridge that has never been used, the water fountains installed by the Ghurkhas that no longer

work, the museum at Mamankhe that nobody visits, the cobbled paths created by WWF that nobody wants to walk on, and so

on.

I like to think that that contact and the intent behind the small practical things we were able to do were the reasons why we

all came back wreathed in silk scarves.